Habit

I enrolled in a philosophy seminar entitled "Free Will and Determinism" during my first semester at the University of Pennsylvania. As the name suggests, we explored questions like:

Why do humans behave as they do?

What is volitional and what is automatic?

What is modifiable and what is inevitable?

We spent class in active debate over the writings of prominent philosophers, some who extolled the power of human choice and others who asserted the methodical machinery governing human behavior.

With the advent of advanced neuroimaging techniques, scientists now have a more objective understanding of the basis for human behavior.

In "The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business," Charles Duhigg expounds on the science of habit, the science guiding human behavior. Although humans would like to consider themselves complex beings executing complex decisions, most of the time this isn't the case.

Active thinking about every single decision of your day would be tremendously inefficient. You simply ain't got time for that. Humans rely on automatic behaviors to execute a majority of mental and motor tasks. These automatic behaviors are called habits.

Why you have habits

What guides your habits

How to change your habits

Why you have habits

Habits offer a significant evolutionary advantage: automatic behaviors simplify your life. Being able to execute routine tasks without actively thinking allows you to allocate mental computing power to other more pressing issues.

Because the way you walk to work is programmed, you can talk on the phone or rehearse your presentation rather than focus on every left and right turn you need to take.

Because the way you tie your shoes is programmed, you can watch television or speak with a loved one while your hands effortlessly execute an intricate motor task.

Habits--subconscious, automatic behaviors that don't require active decision making--increase human efficiency by freeing up time for other activities.

What guides your habits

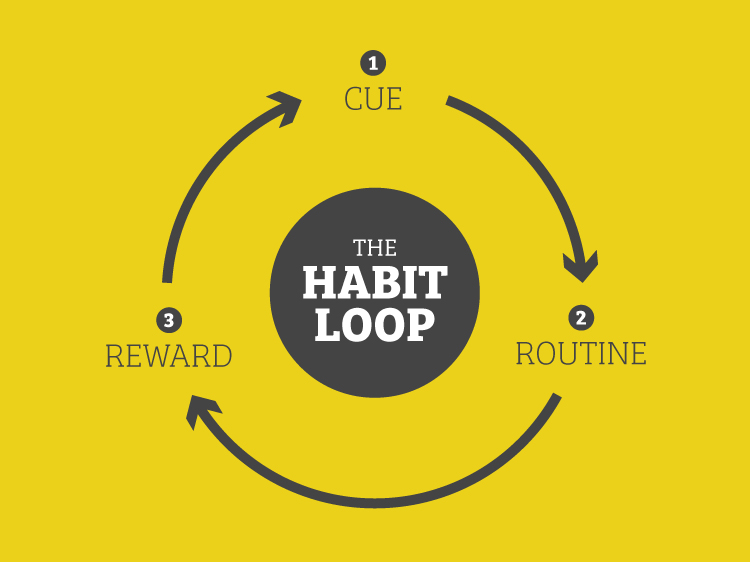

There are three components to the Habit Loop: Cue, Routine, Reward.

Okay, now you understand why you have habits, but how did these habits develop in the first place?

Habits are triggered by cues that lead to routines that lead to rewards. Duhigg terms this process the Habit Loop.

Humans are pleasure mongers and constantly seek rewards. If a particular routine produces a worthwhile reward, the routine will be reinforced; however if the outcome is neutral or negative,the routine will likely be extinguished.

Whether a good habit or a bad habit, the same habit machinery drives behavior: Cue, Routine, Reward.

Going to the gym every morning before work? Good habit.

Smoking every time you feel stressed? Bad habit.

Brushing your teeth every morning? Good habit.

Squandering time on Facebook every five minutes? Bad habit.

In each of these cases, Duhigg would argue, you aren't actively thinking. You are simply responding to cues in your environment: your gym bag next to the front door, your feeling stressed, your bad breath, your being bored. These cues trigger routines: going to the gym, smoking, brushing your teeth, Facebooking. And these routines produce rewards: exercise-induced endorphin rush, feeling relaxed, minty tingle in your mouth, seeing what your friends are up to.

When you begin to anticipate and crave these rewards, control of these actions shifts from your conscious prefrontal cortex to your subconscious brainstem.

How to change your habits

Do you have habits that you'd like to change? Maybe you eat ice cream every night before bed, maybe you binge drink on the weekends, maybe you bite your nails, maybe you smoke cigarettes.

Whatever the bad habit may be, it can be extremely difficult to change. But why?

Humans depend on habits. Simply trying to stop a behavior--and foregoing whatever reward a routine produces--will likely fail. Habits can't be eliminated, but rather replaced.

Duhigg argues that cues and rewards can't be avoided. The trick to improving behavior is to maintain the same cue and reward while switching out the routine.

Smoking is a classic example. The next time a stressful situation cues you to routinely smoke a cigarette in order to get a relaxation reward, instead replace the routine with a cup of tea or a phone call to a friend. The cue and the reward remain the same, but the routine changes. The result is a happy brain maintaining automatic behaviors and still getting a relaxation reward.